Attention Gautam Gambhir: Poor Pitches are a Bad Idea

For some time now Indian cricket coaches and captains have been pushing for curators to make pitches that break up and start turning on day one of a test match. The logic has been that Indian cricketers are past masters of spin while foreigners have trouble with the turning ball and would not have the bowlers to exploit the pitch. Both assertions are incorrect.

Foreign spinners are just as good at exploiting Indian conditions and on occasion part-time bowlers like Joe Root, Travis Head, Glen Phillips and now Aiden Markram have shown that they can strike vital blows in a game.

Myth One: Foreigners don’t have the spinners

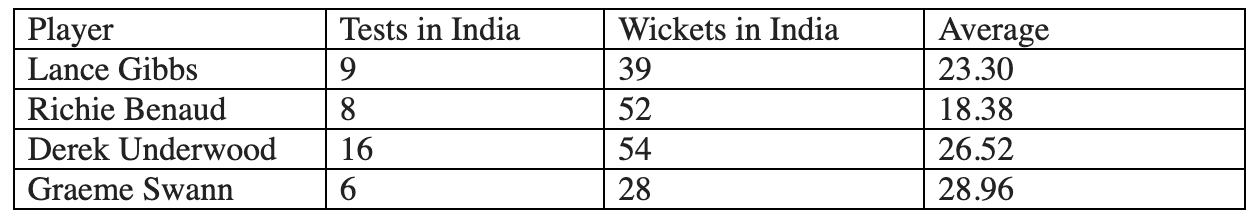

I went through the record of some of the great and not so great spinners who have played in India and their statistics belie the claim that Indians are totally comfortable with spin:

Gibbs, Benaud, Swann, and Underwood were world class spinners who thrived on Indian wickets and had low bowling averages. So the simple question is, how did spinning tracks help? The fact is that Gibbs toured India with three West Indies teams and in each tour came away victorious. Benaud’s record of 52 wickets in 8 tests is phenomenal since leg spinners tend to have a hard time in India. Swann single-handedly led the English bowling in 2012-2103 to a 2-1 victory over India. The fact is that great spinners will generally do well anywhere and to have the arrogance to think you can play them because you are genetically programmed to do so is funny.

The exceptions to the list of great spinners are Shane Warne and Muttiah Muralitharan whose record in India is ordinary. Murali got 40 wickets in 11 tests at an average of 40 while Warne was equally poor with 34 wickets in 9 tests at an average of 43. Even less talented and part-time spinners have done well in India.

Steve O’Keefe whose name has not been heard of after a short test career took 19 wickets in four tests at an average of 23 in the 2016-2017 in India. Part time England spinner Joe Root has been effective enough to take 16 wickets in India with best figures in an innings of 5/8. But the story of the two New Zealand spinners Santner and Patel is a cautionary one on the dubious theory of preparing bad wickets.

Before the 2024-2025 home series against New Zealand, India was sitting pretty in the World Test Championship rankings. Even a 1-0 win would have seen India through to the finals of the championship at Lords. But India lost badly, 3-0, to New Zealand. In the first test Henry and O’Rourke were able to bowl out India in the first innings and then, a Kane Willamson less New Zealand, scored 110 in the fourth innings to win the test.

In the second test at Pune, Mitchell Santner took 7 in an innings while the part-time spin of Glen Phillips was good enough to take two wickets. In the second innings, Santner took six, Ayaaz Patel two, and Phillips bowled 16 overs to take another wicket. When a part-time spinner gets 16 overs in an innings it speaks volumes for the way the batting side is playing.

In the third test, Patel took 11 in the match to spin New Zealand to victory. India could not chase a target of 147, sound familiar? And Phillips took three in the second innings while Santer did not play in the game.

India was humiliated in the series and then had to play a win or go home series in Australia. Once Jasprit Bumrah got injured the rest of India’s bowling was exposed as not being effective. South Africa went on to play Australia and a brilliant Markram century saw them win the championship.

Myth two: Indian pacers cannot do the job

When Kapil Dev spearheaded the attack he was the only world-class bowler in the team and he won India a home series against a highly rated Pakistani side. Now India has Bumrah, Siraj as well as some new pace bowlers with potential.

Making wickets that help the pacers means ones that have a true bounce — which also aids batting — and gives encouragement to the bowlers. Bumrah was good enough to take five wickets on a spin friendly wicket in Eden Gardens. Imagine what he could do on a wicket that gave him more assistance?

Myth three: IPL talent will prosper in test matches

There are very few players who can play tests, ODIs, and T20s with equal aplomb. Sachin Tendulkar, Viv Richards, Gordon Greenidge, and Chris Gayle come to mind. Of course neither Richards nor Greenidge played a T20 but their brutal hitting would have set alight stadiums in the twenty over version of the game. And then, of course, there was Garry Sobers who showed in England’s first class limited over games that he was supremely destructive with both bat and ball.

Most players, however, fall in either the test or limited overs categories. Pujara was a fine test bat but not suited for T20. Neither are Root or Steve Smith. Glenn Maxwell, on the other hand, may be the most talented player in that category.

India needs to recognize that to succeed in tests you need specialist batsmen and not Washington Sundar and Axar Patel who are better suited for the one day game. While Pujara has retired, Ajinkya Rahane is available. Rahane has real test credentials and was a great captain because he took what due to injuries was in effect an India C team to a series victory in Australia after Virat Kohli ran away on maternity leave. The selectors should also go into the Ranji Trophy and see who can play in the test side.

To sum up, sporting wickets produce great contests and while young Indians may obsess over T20, the fact is that the other major cricketing nations of the world—England, Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa—take Test cricket seriously as reflected by the effort they put in to the game and the crowded stadiums in these countries that watch test cricket. Gautam Gambhir needs to stop talking and understand why bad pitches can hurt India just as badly as the opposition.

(Amit Gupta is an External Fellow of the Forum of Federations Ottawa and is completing a book on the BCCI and global cricket. The views in the article are personal.)