RIGHT ANGLE – Bihar Lessons

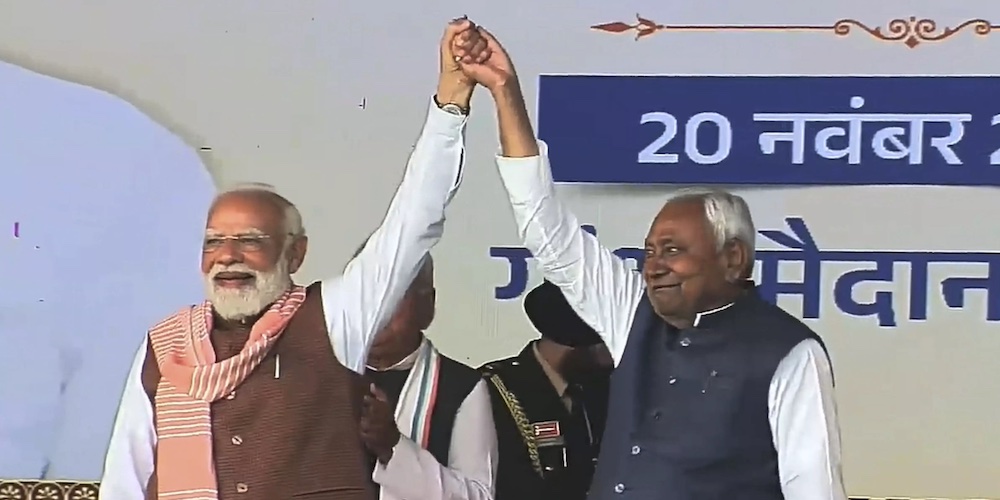

The National Democratic Alliance (NDA) has begun its fresh innings of governing Bihar under the leadership of the redoubtable Nitish Kumar for the tenth time.

The NDA’s victory in the just concluded elections in Bihar highlights several key lessons for the major political players, primarily emphasising the importance of a strong, inclusive coalition, effective welfare delivery, and cohesive alliance management.

This victory was largely due to successfully consolidating a broad social base, particularly by securing the return of Chirag Paswan ( now a Union Minister) –led Lok Janshakti Party to the alliance, which brought together upper castes, non-Yadav Other Backward Classes (OBCs), and Dalits. The opposition Mahagathbandhan (MGB) failed to broaden its appeal beyond its core support, leading to its defeat.

Secondly, the performance of the incumbent government and the effective delivery of welfare schemes (such as cash transfers and other state-sponsored initiatives) were significant factors in influencing voter behavior. Voters respond to schemes that are perceived as reliable entitlements rather than one-off inducements.

Thirdly women emerged as a crucial and distinct voting bloc, with a higher turnout than men. Their support for the NDA’s policies was a key factor in the outcome, demonstrating that no party can afford to ignore this demographic as a game-changer.

Fourthly, the NDA’s formula worked due to a clear hierarchy and a stable, unified message, with both the BJP and Nitish Kumar’s JD(U) effectively managing internal dissent to ensure vote transfer among allies. In contrast, the MGB was seen as less cohesive, with a lack of a clear center of gravity.

Fifthly, the election showed that sustained, bottom-up engagement through local networks at the grassroots level holds more sway than campaigns built purely on media spectacle or social media traction. If one would have gone by spectacle of the rallies and campaigns of the Congress supremo Rahul Gandhi and RJD’s Tejashwi Yadav, then the MGB would have got more than 200 in the 243 seats of the state assembly. For the opposition, particularly the Congress party, the results highlighted the need for organisational depth, clear political messaging, and a more disciplined approach to alliance building, moving beyond episodic or personality-driven campaigns.

However, important though the above lessons are, for me what strikes most is that the Indian electorate has become really mature in assessing a leader’s credibility and accessibility, and filtering national narratives through older local infrastructures.

As a political analyst I may be in a distinct minority, but the latest round of Bihar elections has further deepened my belief that electoral outcomes are no longer determined by the ethnic (caste or religion) or the identity factor alone. It is not “the most important thing” that matters. The assumption here is that the “masses” vote along caste or community lines, and thus, are “captive vote banks” – A Dalit will always vote for a Dalit leader, a Yadav will always vote for a Yadav, a Muslim will always vote for a Muslim. But nothing can be more simplistic than this. If masses will always vote along caste or community lines or as a monolithic block , elections would be a simple affair where any caste group which was dominant and had the numbers would automatically win. Had that been the case a Mayawati or an Akhilesh Yadav would never have been defeated or lost power in Uttar Pradesh. The same would have been the case with Lalu Yadav and his son in Bihar.

However, though the old habits and beliefs still persist, the fact remains that after the advent of the Narandra Modi phenomenon in 2014, and in the context of Bihar the image of Nitish Kumar as a capable administrator, the conventional barometers to study elections have outlived their utilities.

Modi has proved the limitations of the often lauded identity politics of caste, creed and region. As in the 2014 General Election, the results of this election have proved beyond any shadow of doubt that people have voted beyond caste lines. And, it is a healthy development. Indian democracy will be much stronger if one votes as an Indian, not as a member of a particular caste or religion.

Unfortunately the dominant sections within the Indian polity, and this includes the intelligentsia, glorify identity politics. For instance, if Yadavs, Muslims and Dalits vote as a block, they laud the phenomenon as consolidation for their respective rights. If somebody opposes this trend, he or she is branded as communal. In this sense, the Bihar electorate has taught these people a good lesson.

If the NDA has won, it is because of its empowering or aspirational politics, be it in the infrastructural development or welfare measures. The incumbent government led by Nitish Kumar and supported by Prime Minister Nrendra Modi appealed to the broad spectrum of society. And those aspirations have nothing to do with religion, caste or any other identity. People wanted development and a better future. In the process, they have rejected the systematic slanders (that continue even today, thanks to its sustenance by the mainstream media dominated by the so-called Left and liberals) that Modi is a deeply divisive figure.

In fact, the Bihar elections have proved once again that the more you demonise Modi, the more sympathy he draws from people at the ground level. The same is the case with baseless allegations against political adversaries. Voters are not impressed by countless allegations against Modi by Rahul Gandhi that do not have any substance whatsoever.

On the other hand, as in many elections over the last 10 years, the one in Bihar proved that in this country of great diversities, there are spaces for leaders who have the nationwide appeal and who conduct a presidential-style campaign by travelling thousands of miles and addressing public meetings, even if these are for local or Assembly elections. In fact, Modi’s has been one of the largest mass outreaches in India’s electoral history. Modi’s support-base cannot be judged strictly in terms of regional or identity politics. This base, if at all, can be judged vertically in terms of class, not of caste or creed or region. And in this class divide, it is obvious that the poor, who are in much larger numbers, had been with Modi, or for that matter with the NDA.

Of course, now the habitual critics will express doubts over the longevity of this government, given the number of times Nitish has left and re-entered the NDA. Of course, during electioneering, Nitish had said that it was a mistake and he would never repeat it. It is perhaps underplayed that Nitish has always risen high in the company of BJP and not the other way round. He became the chief minister of Bihar for the first time in 2000, though for exactly a week (3 March, 2000 to 10 March, 2000) when the BJP-led government at the Centre (under Atal Bihari Vajpayee) released him from the Union cabinet to just have a chance towards an NDA regime in the state. That time, BJP had 39 seats in the Bihar Assembly whereas Nitish’s party had only 18 seats. For that matter, in the 1999 General Elections to Lok Sabha, the BJP had 23 Lok Sabha seats from the then undivided Bihar, whereas JD(U) had only eight. In the 1998 General elections, BJP had 19 Lok Sabha MPs, against 10 from Nitish’s then Samata party.

The point that emerges from above data is that despite the fact that Nitish has been much behind in terms of share of support-base, the BJP leadership has always promoted him. And to such an extent that after he became the chief Minister with a comfortable majority in 2005 in alliance with the BJP, the latter, by and by, ceded space to become a junior partner in every sense of the term.

In other words, until 2005, the BJP was the largest NDA constituent in Bihar, but the then Vajpayee-LK Advani leadership promoted Nitish to the extent that the JD(U), the younger brother to the BJP in Bihar, became the elder brother. In 2020, BJP had more numbers but Modi allowed Nitish to continue as the Chief Minister. The same has been the case this time too, despite the BJP emerging as the single largest party in the Assembly.

As an observer of Indian politics, one has to admit that contrary to the common perceptions, BJP (or its previous incarnation, Jana Sangh) has always been an honest and accommodative partner in the game of alliance politics, but this gesture of the party has rarely been reciprocated. Despite constituting the largest block in the Janata Party after the 1977 elections, it had inadequate representations in Morarji Desai’s cabinet. It had an alliance with Bahujan Samaj Party, once, in Uttar Pradesh, but BSP chief Mayawati stabbed the BJP.

In the 1998 General Elections to Lok Sabha, Biju Patnaik was no more in the scene and all over Odisha people were talking of Vajpayee. And yet the BJP willingly became a junior partner to the newly formed Biju Janata Dal (BJD) led by Naveen Patnaik. In Maharashtra, as long as Shiv Sena was the elder brother, BJP did not have any chance to grow. The party separated in the 2015 Assembly polls of Maharashtra because of Shiv Sena’s reluctance to give adequate seats. The BJP proved its worth by bagging more than double seats than the hitherto elder brother. Even after Shiv Sena’s return to the NDA, it did not get even half of the BJP’s tally in 2019 elections. That its leader Udhav Thackeray betrayed the BJP and went to form the government by disregarding the people’s mandate is a different story.

However, at the moment, Modi-Nitish bonhomie looks too strong to be broken.