RIGHT ANGLE – Constitution is Sacred but Mutable

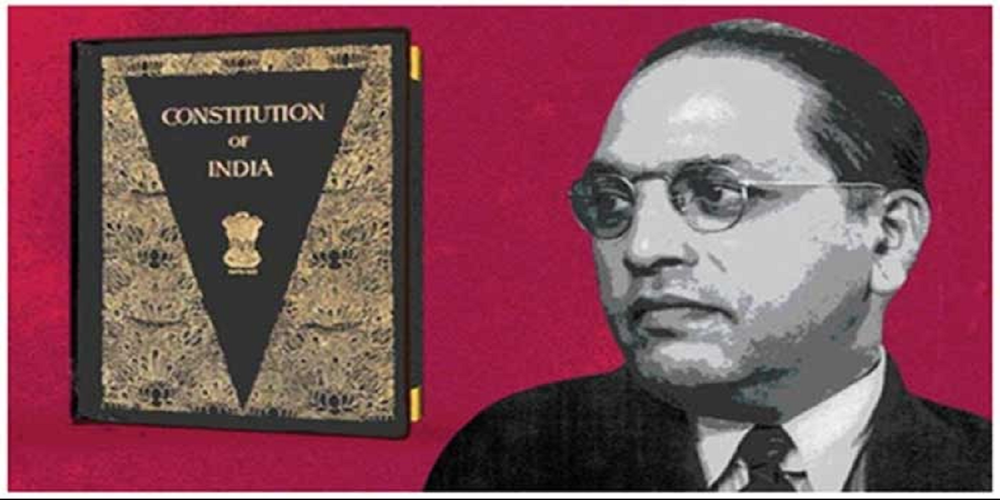

The country just witnessed two day-long deliberations in the Parliament on the Indian constitution. Dispassionately viewed, whether it was the ruling National Democratic Alliance (NDA) members led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi or the members belonging to opposition INDI Alliance led by the Congress supremo Rahul Gandhi, the discussions led to the impression that the Indian Constitution is Dr. B R Ambedkar and Dr. B R Ambedkar is the Indian Constitution. The debate between the treasury benches and the opposition, thus, was confined essentially to who are better followers of Ambedkar.

Ambedkar was the chairman of the drafting committee of the Constituent Assembly. But to describe him as the sole drafter of India’s constitution that some members tried to project is something that would have embarrassed Ambedkar himself. Because, there are many things mentioned in our constitution that Ambedkar, left to himself, would not have even accepted.

Both his admirers and critics will agree that Ambedkar was a champion dissenter in the days of Mahatma Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru. Therefore, it is really surprising that in today’s politics of Narendra Modi and Rahul Gandhi, a word against Ambedkar implies treason.

I shudder to think what would have have happened to veteran editor and author (who was also a senior cabinet minister under late Prime Minister Atal Behari Vajpayee but now a big advisor of the opposition against Narendra Modi) Arun Shourie, who authored a book “Worshipping False Gods : Ambedkar, and the facts which have been erased” in 1997.

In this book, Shourie delved into archival records to ask pertinent questions: Did Ambedkar coordinate his opposition to the freedom struggle with the British? How does his approach to social change contrast with that of Mahatma Gandhi? Did the Constitution spring from him or did it grow as a dynamic living organism? Passionately argued and based on a mountain of facts that it presents, Worshipping False Gods compels us, indeed, to go behind the myths on which discourse is built in India today.

The main problem with Ambedkar was that despite his undoubted scholarship, his prime focus was on the dalits, the community he belonged to, and their empowerment in post-British India. His hatred for the Sanatan Dharma was such that he wanted to penalise even reading Shrutis and Smritis. The point is that he preferred to remain a leader of Dalits rather than becoming a national leader acceptable to all the communities and sections.

Ideally, a constitution must be acceptable to “All”. Ambedkar led the drafting of such a constitution, but that, as he said later, was “against his will” and forced upon him.

On 2 September 1953 while debating how a Governor in the country should be invested with more powers, Dr Ambedkar argued strongly in the Rajya Sabha in favour of amending the constitution. And while doing so, he said : “Sir, my friends tell me that I have made the Constitution. But I am quite prepared to say that I shall be the first person to burn it out. I do not want it. It does not suit anybody”. He thus advocated strongly that the constitution needs to be amended “if our people want to carry on”.

It is equally interesting to note that Ambedkar was also not in favour of the idea of a Constituent Assembly, though he later became a part of it to chair the drafting committee.

As Vineeth Krishna, editor of the Centre for Law and Policy Research has aptly pointed out, while addressing on 6 May 1945 a gathering of the All-India Scheduled Castes Federation, Ambekar asked ‘Should there be a Constituent Assembly, charged with the function of making a Constitution?’. For him, the answer was a firm ‘No’. He stated that a Constituent Assembly was ‘absolutely superfluous. I regard it as a most dangerous project, which may involve this country in a civil war’. In his speech, he provided two sets of reasons for his position:

First, he felt that, unlike the time when the Americans were framing their Constitution in the late 1700s, ‘Constitutional ideas and constitutional forms are ready at hand’. India had to merely pick and choose from a few ready-made constitutional designs. Further, there was not a great deal of dispute among Indians regarding various constitutional features. The Government of India Act 1935 pretty much contained the Constitution of India, and all one had to do was to remove those sections of the Act which were inconsistent with independent India’s sovereignty. Therefore, a Constituent Assembly was not required, argued Ambedkar.

The only outstanding problem according to Ambedkar was the ‘communal problem’. And he felt that a Constituent Assembly could not and should not resolve the communal problem. This is strikingly different from Gandhi and the Congress, who believed that a Constituent Assembly was the solution to the communal problem. For Ambedkar, the Constituent Assembly was a strategy of solving the communal problem through ‘methods instead of principles’.

He was aware that the election of members to the Constituent Assembly (the distribution of seats among different communities) was itself an issue that came under the ambit of the communal problem. The thrust of Ambedkar’s opposition to a Constituent Assembly was his concern that the Indian constitution-making process would be dominated by a few groups, and a Constitution would be imposed on less politically powerful communities without their consent.

In fact, many scholars of the Indian constitution do agree that the Constituent Assembly was not a true representative body of the Indian people. Its members were not elected by the Indian people. In fact, it was created because of the proposals of the British rulers through their “Cabinet Mission” plan. It was totally dominated by the Congress members. No wonder why British Constitutional expert Granville Austin remarked that “the Constituent Assembly was only a party body in a one-party country. It was only the Indian Congress Assembly”.

Another important criticism is that the Constitution was a stitching together of different portions taken out of different foreign Constitutions — a “bag of borrowings”. It does not reflect the specialities of Indian culture or heritage.

Dr Ambedkar agreed that it was framed after “ransacking all the known Constitutions across the world”. It is a broad replica of the British Government’s Government of India Act of 1935, according to another British scholar Sir Ivor Jennings. And then few provisions were copied from other countries’ constitutions. Fundamental Rights were taken from the American Bills of Rights. Directive Principles were adopted from the Irish Constitution. From British Constitutional principles, the political system of Parliamentary democracy was taken. The federal relation between Union and the State was adopted from the Constitution of Canada. The rights and powers of Parliament and Assembly members were taken from the Australian Constitution. Thus goes the long list of “ransacked” Constitutions.

The point that emerges from all this is that whatever its admirers may say, the fact remains that the constitution as it was drafted in 1949 and enforced in 1950 had predominantly western features that were not necessarily in tune with what an oriental country with arguably the richest culture of the world really needed. And that explains why this constitution has been amended as many as 106 times until September 2023, and quite a few are waiting for the approval of the parliament.

It is instructive to note here that the Government of India had established the National Commission to Review the Working of the Constitution (NCRWC) in 2000 to examine the Constitution and suggest amendments. The commission’s terms of reference included:

• Examining how the Constitution can respond to the changing needs of the country towards efficient, smooth and effective system of governance and socio-economic development of modern India

• Recommending changes to the Constitution without interfering with its basic structure or features

The Commission, headed by Shri Justice M.N. Venkatachalaiah, had made various recommendations in 2002 pertaining to (i) Fundamental Rights, Directive Principles and Fundamental Duties; (ii) Electoral Processes and Political Parties; (iii) Parliament and State Legislatures; (iv) Executive and Public Administration; (v) The Judiciary; (vi) Union-State Relations; (vii) Decentralization and Devolution; and (viii) Pace of Socio-Economic Change and Development. The recommendations involve amendments to the Constitution, legislative measures and executive action.

Obviously, the then Vajpayee government could not implement these recommendations because it could not create the necessary political consensus on them. But the point is unmistakable. And that is that amending the constitution is not killing or murdering the constitution, something that the likes of Rahul Gandhi will like us to believe.

Every successful amendment, brought out by the ruling governments from time to time, needs to be seen as people’s changed aspirations. Whatever was proposed or drafted by Ambedkar’s committee in 1949 cannot remain sacred for all time to come. The Constitution, after all, is a “living document” that can change from time to time.