Can India join the Five Eyes?

Strange as it may seem, but it is true that the Five Eyes intelligence partnership, which Canada is relying on the most to prove its charges of the Indian involvement in the murder of a Khalistani terrorist and gathering intelligence on other such terrorists on its soil, is potentially open for India being a part of it along with Japan, Germany and South Korea.

This idea has emanated from the United States, arguably the leader of the Five-Eyes. A Congressional subcommittee on Intelligence and Special Operations had asked in 2022 the Director of National Intelligence, and the Secretary for Defence to consider the expansion of the Five Eyes. Since then, the idea has been under discussion among the policy-makers.

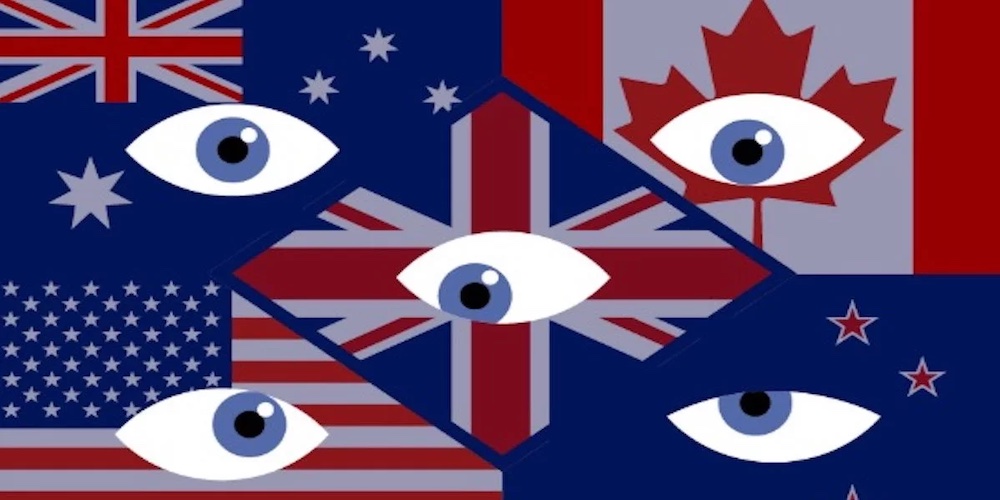

Incidentally, the “Five Eyes” multilateral intelligence-sharing arrangement, comprising the major intelligence services of Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and the United States, was formed in 1946 when the Cold War was emerging, with Russia being seen as the biggest threat to the democracy and the Western value-system.

It has been described variously as “the most exclusive intelligence sharing club in the world,” “the world’s leading intelligence-sharing network,” “the world’s oldest intelligence partnership,” and “the world’s deepest and most comprehensive collaboration among spy services”.

The origin of the Five Eyes could be traced to the decision by the then British Prime Minister Winston Churchill in 1941 to include the US in one of the greatest secrets of all time – that the UK (with help from the Poles and French) had broken the German Enigma cipher system. The secret (known as ULTRA) was very tightly controlled in the UK, and the idea of sharing it with the Americans was not without risk, but it proved to be an astute political calculation.

After the war, this Anglo-American cooperation was formalised into the 1946 UKUSA agreement. Canada became a part of it in 1948, and Australia and New Zealand in 1956 through what was said “their Dominion status within the British Commonwealth”.

The appellation of the group was shorthand for the security classification of intelligence documents shared between these countries: “SECRET — AUS/CAN/NZ/UK/US EYES ONLY.”

The agreement was so secret that Australian Prime Minister Gough Whitlam reportedly was not informed of its existence until 1973. No government officially acknowledged the arrangement by name until 1999, when the director of Australia’s Defence Signals Directorate (DSD) disclosed his country’s cooperation “with counterpart signals intelligence organizations overseas under the UKUSA relationship”.

Indeed, the contents of the UKUSA agreement were officially disclosed to the public for the first time in June 2010.

Each of the Five Eyes states is said to be conducting interception, collection, acquisition, analysis and decryption activities, sharing all intelligence information obtained with the others by default.

However, it is to be noted that the foundation of their intelligence- activities happens to be signals intelligence-sharing (i.e., sharing foreign intelligence gathered from communications and information systems). With the passage of time, other cooperative areas have been added to include human intelligence-sharing (i.e., information gleaned from personal contacts), technological co-development, and military equipment and communications interoperability.

Besides, intelligence-sharing agreements have now expanded beyond the core Five Eyes to what are 9 Eyes( with the addition of Denmark, France, the Netherlands and Norway), 14 Eyes ( 9 Eyes plus of Germany, Belgium, Italy, Spain and Sweden and 41 Eyes ( all of the above, with the addition of the allied coalition in Afghanistan).

However, it is to be noted that the scope of other Eyes is limited to sharing some of the resources of the Five Eyes, not all. They cannot access all the data of the Five Eyes.

Be that as it may, in a fast-changing world, Five Eyes are beset with new challenges. Noteworthy among them are the following:

First, although members cooperate formally in diverse areas of intelligence, such as human intelligence (HUMINT), covert action, counterintelligence security provisions for data handling, and the preparation of joint estimates, the core of these multilateral arrangements is signals intelligence (SIGINT), a broad series of operations that target electromagnetic emissions. But these are said to be inadequate in an age of satellites, long-range reconnaissance aircraft and the internet. Therefore, there are now talks of the members expanding their respective technology- industrial base and initiating closer government-private interactions.

Secondly, the “Anglophonic” or “Anglo-Saxon” identity of the Five Eyes is getting diluted with the rapid demographic changes, thanks to the waves of immigration from outside the Anglosphere in each of them. The gradual embrace of multiculturalism is diminishing the hitherto shared sentiment that citizens are exclusively English kin and intelligence is vital to protect their “civilization, culture, and race”.

This, perhaps, explains why citizens in these countries are increasingly questioning the lack of transparency and accountability in Five Eyes’ operations. The alliance’s secretive nature means that citizens have little insight into how their data is being collected, shared, and used, making it difficult to hold governments accountable for potential abuses of power. As it is, Edward Snowden’s 2013 revelations peeled back the curtain on the extensive data harvesting activities of the alliance, throwing a spotlight on the precarious balance between security and individual privacy rights.

Thirdly, there have been discordant voices against the increasing dominance of the United States over the other four partners. Andrew O’Neil , Professor of Political Science and Research Dean at Australia’s Griffith University has argued how the U.S. dictates in hierarchical fashion the terms and conditions of how the Five Eyes network functions, and that junior partners have little alternative but to fall in line if they want to preserve the flow of high-grade intelligence from Washington.

It is said that the dominant U.S. has periodically used intelligence “cut-offs” as a stick to pressure its allies into adopting policies that are more aligned with that of Washington. Among the examples cited are the U.S. government’s veiled threat to Britain during the Huawei controversy; the U.S. effectively suspending New Zealand from the trilateral ANZUS alliance when Wellington refused in the mid-1980s to allow American nuclear-capable warships to dock in its ports; the U.S. not supporting the UK during the Suez Crisis(1956); the UK’s unwillingness to become involved in the Vietnam War; the flawed intelligence which led to the 2003 invasion of Iraq; and a slew of espionage setbacks, from Kim Philby and George Blake in the 1960s to Aldrich Ames and Robert Hanssen in the 1990s/2000s.

Fourthly, it is argued that the Five Eyes alliance’s greatest challenge today lies in the fact that it no longer faces a single predominant threat. The intelligence communities of all five nations now contend with self-radicalized terrorists at home, an entire new domain of cyber threats, and Russia and China. Can the Five Eyes partnership survive in this environment while minimizing painful trade-offs and capability cutbacks? This question has no easy answer.

This, possibly, is the reason why policy-elites in Washington are mooting the idea of expanding the alliance and “the circle of trust” to other like-minded democracies like India. And there are analysts like Mohamed Zeeshan, who argue that India should be part of this expanded group if invited. Because, it would lead to privileged access to the product from state-of-the-art intelligence capabilities, especially from Britain and America.

“It would mean increased opportunities for training and technology from the top of the shelf. It would also significantly improve India’s preparedness in confronting threats such as cross-border infiltration in Kashmir and incursions along the difficult border with China. Given the Five Eyes’ more global intelligence presence, it would also help India expand its own influence and presence, particularly if Indian diplomatic missions around the world can benefit from US intelligence on the countries where they operate.

“There are many other advantages as well: A member of the Five Eyes is the most direct beneficiary of US foreign policy influence and hard power, meaning stronger bargaining power vis- à-vis other countries, stronger national passports and more travel freedom, and increased security for their citizens overseas. A closer relationship can extend to American security guarantees when under attack from an enemy”, Zeeshan argues.

However, any expansion of the Five Eyes appears to be easier said than done. All told, despite occasional differences, all the members of the Five Eyes alliance do share the same strategic or geopolitical outlook. This may not be the case with India, which values its “strategic autonomy” and has close ties with Russia. And without a shared perception of threats, it is difficult to share intelligence and respect the circle of trust.